In his documentary about legendary Brazilian photographer Sebastião Salgado, Wim Wenders teamed up to work with Salgado's son Juliano. Together they made something unique

One of the incidental pleasures of the Cannes film festival

is its Special Screenings section: here you will find tasty, intriguing

little films that won't necessarily be comfortable alongside the big

beasts of the official competition, or happy with being bracketed with

the flash newcomers in Un Certain Regard. Such a film is The Salt of the Earth, a gentle, beguiling biography of legendary Brazilian photographer Sebastião Salgado,

whose amazing persistence and facility for empathising with his

subjects has produced brilliant work for more than four decades.

The Salt of the Earth is directed by German auteur Wim Wenders, together with Salgado's son Juliano, himself a film-maker though one – if we're being honest – not yet to achieve the heights that Wenders has. But Salgado Jr certainly makes a key contribution: not only in supplying footage of trips on which he accompanied his father before this documentary was mooted, but also getting on film some intimate scenes of the now-elderly Salgado pottering around his old family farm in Brazil, reflecting on his relationship with his own father.

It certainly helps The Salt of the Earth that Wenders, by some distance the senior partner behind the camera, was happy to put what he calls "the ego thing" to one side, and share credit with Juliano. It turns out that he and Salgado Jr each had their own, separate films planned, but after long-running discussions, decided to merge resources and collaborate.

"You know," says Wenders, now 68, soft-voiced and, thankfully, no longer sporting that rather disconcerting ageing-rocker hairdo he had in recent years: "Juliano and I became friends. I looked at his stuff and thought it was good, and then we realised if we both overcame this thing, being the sole 'author', we could make something bigger, more than the sum of our two films."

Wenders says he had originally been asked to make a film of Salgado's Genesis project, in which Salgado planned to photograph those areas of the planet still untouched by human development. (Rather happily, as The Salt of the Earth tells us, Salgado found more than half of its surface essentially undisturbed.) "When I first started the film, I thought I would just do a few interviews," says Wenders. "Then I realised I better travel with him, and then before I knew it I went to Brazil. Then a year had passed and we had shot hundreds of hours of footage."

Juliano Salgado: 'My dad was very touched, as he was seeing him how I saw him.' For his part, Juliano had been going (initially reluctantly) with his father on trips for the past few years, and as an aspiring director had shot footage in Amazonia, Siberia and Indonesia, among other places. "I didn't want to go at first. I mean, when you know that you will be stuck in some isolated place with your dad … but he insisted. He said that as he was getting old, he wanted to keep a record – but I really think he just wanted me to be there. He knew it would be an experience."

The way he tells it, these trips improved their relationship no end, especially when Juliano showed his father his edits. "He was very touched, as he was seeing how I saw him."

Having spent time at film school in London, and with a few credits under his belt, a documentary about his famous father would appear to have been a natural next step. Any resentment at the appearance of Wenders on the scene seems to have disappeared once the pair started discussing how they would turn Sebastião's life and work into a dramatically interesting film. Wenders says the key was the photographer's emotional and psychological trauma after spending the genocide in the mid-90s, followed by his subsequent return to Brazil and involvement in rainforest restoration.

"You have to understand that he came to the end of something. He came to the heart of darkness; the hell had really gotten to him and I don't think he was able to live. He may not have found the way out of it if it hadn't been for his new encounter with nature. It was a redemption. Planting rainforest, reanimating dead ground, pulled him out of the terrible hole he was in and he reinvented himself as well as his photography."

In The Salt of the Earth, we see Salgado, along with his wife Lélia, divert their energy away from photography to try to reclaim the drought-stricken farm; the idea of a garden gradually evolved into a national park, with millions of replanted trees. It's this change of direction that also saw a reinvigorated Salgado embark on Genesis.

Juliano says this redemptive narrative concurred with his own ideas about how to tell his father's story. "He had to reinvent himself. He has always been very empathetic, and using his photos to communicate with people, but now has something to transmit that is not simply a message about complex social problems. It's something more positive – how you can create something."

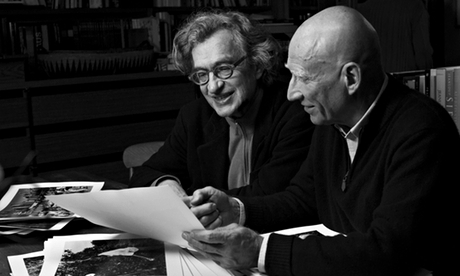

Wim Wenders (left) with Sebastião Salgado.

Salgado is still arguably most famous for a set of pictures he made in the mid-80s, documenting the chaotic, nightmarish conditions inside a Brazilian mountain gold mine called Serra Pelada; in their teeming, otherworldly

brilliance they had all the force of a Hieronymus Bosch painting.

Wenders says he discovered them in the late 80s in a gallery in Los

Angeles, and they "blew his mind". Not only does The Salt of the Earth

fill in some of the gaps – the miners, it turns out, were not illegal or

enslaved, but a huge cross section of Brazilian society pouring in for a

gold rush – but also shows how the pictures sparked Salgado's

inclination for long-term, large-scale projects.

Wim Wenders (left) with Sebastião Salgado.

Salgado is still arguably most famous for a set of pictures he made in the mid-80s, documenting the chaotic, nightmarish conditions inside a Brazilian mountain gold mine called Serra Pelada; in their teeming, otherworldly

brilliance they had all the force of a Hieronymus Bosch painting.

Wenders says he discovered them in the late 80s in a gallery in Los

Angeles, and they "blew his mind". Not only does The Salt of the Earth

fill in some of the gaps – the miners, it turns out, were not illegal or

enslaved, but a huge cross section of Brazilian society pouring in for a

gold rush – but also shows how the pictures sparked Salgado's

inclination for long-term, large-scale projects.

The film also shows that Lélia is the hitherto-unrecognised figure in Salgado's success: a key instigator of the conception, design, and selling of the work.

Juliano is keen to talk up her role: trained as an architect, she gave up work after her second son, Rodrigo, was born with Down's syndrome. "It's really both of their work. The thing is, she didn't want to travel to go to these places, most of them were pretty tough and dangerous. Before she got involved, my father's career wasn't going too well, but when they started doing them together things started happening."

It was her participation, he says, that turned his father's projects into serious social analysis – Workers, Exodus, et al – rather than just stories. "But the really intimidating thing about my parents is everything they do, they do really well."

Lucky for him, then, that he had a figure as august as Wenders alongside. Despite admitting he was a little afraid of "being eaten by the history of cinema", Juliano says the film definitely benefited ("I couldn't have done the interviews – my relationship with my dad is too charged").

Wenders says he felt the same: "It only mattered we got across the most complex idea of Sebastião. My approach as an outsider, his approach as the son – if we threw them together we could make something quite unique. The outcome is better than something I could have done myself. We could have both made films on our own, but neither would have been as big as this one."

The Salt of the Earth is directed by German auteur Wim Wenders, together with Salgado's son Juliano, himself a film-maker though one – if we're being honest – not yet to achieve the heights that Wenders has. But Salgado Jr certainly makes a key contribution: not only in supplying footage of trips on which he accompanied his father before this documentary was mooted, but also getting on film some intimate scenes of the now-elderly Salgado pottering around his old family farm in Brazil, reflecting on his relationship with his own father.

It certainly helps The Salt of the Earth that Wenders, by some distance the senior partner behind the camera, was happy to put what he calls "the ego thing" to one side, and share credit with Juliano. It turns out that he and Salgado Jr each had their own, separate films planned, but after long-running discussions, decided to merge resources and collaborate.

"You know," says Wenders, now 68, soft-voiced and, thankfully, no longer sporting that rather disconcerting ageing-rocker hairdo he had in recent years: "Juliano and I became friends. I looked at his stuff and thought it was good, and then we realised if we both overcame this thing, being the sole 'author', we could make something bigger, more than the sum of our two films."

Wenders says he had originally been asked to make a film of Salgado's Genesis project, in which Salgado planned to photograph those areas of the planet still untouched by human development. (Rather happily, as The Salt of the Earth tells us, Salgado found more than half of its surface essentially undisturbed.) "When I first started the film, I thought I would just do a few interviews," says Wenders. "Then I realised I better travel with him, and then before I knew it I went to Brazil. Then a year had passed and we had shot hundreds of hours of footage."

Juliano Salgado: 'My dad was very touched, as he was seeing him how I saw him.' For his part, Juliano had been going (initially reluctantly) with his father on trips for the past few years, and as an aspiring director had shot footage in Amazonia, Siberia and Indonesia, among other places. "I didn't want to go at first. I mean, when you know that you will be stuck in some isolated place with your dad … but he insisted. He said that as he was getting old, he wanted to keep a record – but I really think he just wanted me to be there. He knew it would be an experience."

The way he tells it, these trips improved their relationship no end, especially when Juliano showed his father his edits. "He was very touched, as he was seeing how I saw him."

Having spent time at film school in London, and with a few credits under his belt, a documentary about his famous father would appear to have been a natural next step. Any resentment at the appearance of Wenders on the scene seems to have disappeared once the pair started discussing how they would turn Sebastião's life and work into a dramatically interesting film. Wenders says the key was the photographer's emotional and psychological trauma after spending the genocide in the mid-90s, followed by his subsequent return to Brazil and involvement in rainforest restoration.

"You have to understand that he came to the end of something. He came to the heart of darkness; the hell had really gotten to him and I don't think he was able to live. He may not have found the way out of it if it hadn't been for his new encounter with nature. It was a redemption. Planting rainforest, reanimating dead ground, pulled him out of the terrible hole he was in and he reinvented himself as well as his photography."

In The Salt of the Earth, we see Salgado, along with his wife Lélia, divert their energy away from photography to try to reclaim the drought-stricken farm; the idea of a garden gradually evolved into a national park, with millions of replanted trees. It's this change of direction that also saw a reinvigorated Salgado embark on Genesis.

Juliano says this redemptive narrative concurred with his own ideas about how to tell his father's story. "He had to reinvent himself. He has always been very empathetic, and using his photos to communicate with people, but now has something to transmit that is not simply a message about complex social problems. It's something more positive – how you can create something."

Wim Wenders (left) with Sebastião Salgado.

Salgado is still arguably most famous for a set of pictures he made in the mid-80s, documenting the chaotic, nightmarish conditions inside a Brazilian mountain gold mine called Serra Pelada; in their teeming, otherworldly

brilliance they had all the force of a Hieronymus Bosch painting.

Wenders says he discovered them in the late 80s in a gallery in Los

Angeles, and they "blew his mind". Not only does The Salt of the Earth

fill in some of the gaps – the miners, it turns out, were not illegal or

enslaved, but a huge cross section of Brazilian society pouring in for a

gold rush – but also shows how the pictures sparked Salgado's

inclination for long-term, large-scale projects.

Wim Wenders (left) with Sebastião Salgado.

Salgado is still arguably most famous for a set of pictures he made in the mid-80s, documenting the chaotic, nightmarish conditions inside a Brazilian mountain gold mine called Serra Pelada; in their teeming, otherworldly

brilliance they had all the force of a Hieronymus Bosch painting.

Wenders says he discovered them in the late 80s in a gallery in Los

Angeles, and they "blew his mind". Not only does The Salt of the Earth

fill in some of the gaps – the miners, it turns out, were not illegal or

enslaved, but a huge cross section of Brazilian society pouring in for a

gold rush – but also shows how the pictures sparked Salgado's

inclination for long-term, large-scale projects.The film also shows that Lélia is the hitherto-unrecognised figure in Salgado's success: a key instigator of the conception, design, and selling of the work.

Juliano is keen to talk up her role: trained as an architect, she gave up work after her second son, Rodrigo, was born with Down's syndrome. "It's really both of their work. The thing is, she didn't want to travel to go to these places, most of them were pretty tough and dangerous. Before she got involved, my father's career wasn't going too well, but when they started doing them together things started happening."

It was her participation, he says, that turned his father's projects into serious social analysis – Workers, Exodus, et al – rather than just stories. "But the really intimidating thing about my parents is everything they do, they do really well."

Lucky for him, then, that he had a figure as august as Wenders alongside. Despite admitting he was a little afraid of "being eaten by the history of cinema", Juliano says the film definitely benefited ("I couldn't have done the interviews – my relationship with my dad is too charged").

Wenders says he felt the same: "It only mattered we got across the most complex idea of Sebastião. My approach as an outsider, his approach as the son – if we threw them together we could make something quite unique. The outcome is better than something I could have done myself. We could have both made films on our own, but neither would have been as big as this one."